New Men: “Playing the sensitive lad”

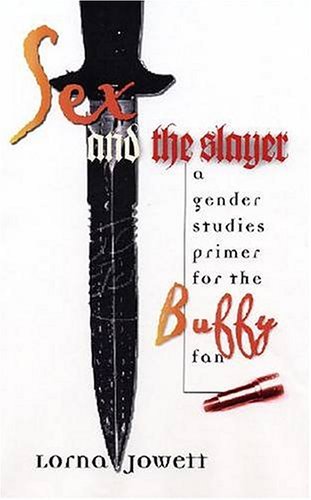

This essay is Chapter Five from Sex and the Slayer (Wesleyan U P 2004). It is published here with the kind permission of Professor Jowett and Wesleyan. Go here to order the book from Amazon.com.

[1]

It follows that in trying to destabilize traditional representations of

femininity, especially through role reversal, Buffy

must offer a concomitant alternative version of masculinity. Producer Fran Rubel

Kuzui articulates this when she says, “You can educate your daughters to be

Slayers, but you have to educate your sons to be Xanders” (in Golden and

Holder 1998: 248). In 1995 Thomas suggested that the British television

detective series Inspector Morse

demonstrated “the extent to which feminist influences are discernible in this

example of quality popular culture, particularly in its representations of

masculinity” (1997: 184). Television melodrama and soap in particular have

addressed masculinity because they are concerned with family and the domestic,

traditionally “feminine” areas (Torres 1993: 288). Saxey notes with some

surprise that in Buffy fan fiction “it is the males who are persistently tortured

by doubt” and wonders why “slash readers and writers wish to explore the

suffering of these often sensitive, non-traditional male figures, while female

characters more often enjoy less emotionally painful treatment” (2001: 201),

and I would suggest that it is partly because masculinity is being so visibly

renegotiated in pop-cultural forms. As noted in the last chapter, “good” new

masculinity contrasts with “bad” tough-guy masculinity by being

“feminized,” passive, sensitive, weak, and emotional, and this contrast is

partly about the separation of gender and behavior in the new men.

[1]

It follows that in trying to destabilize traditional representations of

femininity, especially through role reversal, Buffy

must offer a concomitant alternative version of masculinity. Producer Fran Rubel

Kuzui articulates this when she says, “You can educate your daughters to be

Slayers, but you have to educate your sons to be Xanders” (in Golden and

Holder 1998: 248). In 1995 Thomas suggested that the British television

detective series Inspector Morse

demonstrated “the extent to which feminist influences are discernible in this

example of quality popular culture, particularly in its representations of

masculinity” (1997: 184). Television melodrama and soap in particular have

addressed masculinity because they are concerned with family and the domestic,

traditionally “feminine” areas (Torres 1993: 288). Saxey notes with some

surprise that in Buffy fan fiction “it is the males who are persistently tortured

by doubt” and wonders why “slash readers and writers wish to explore the

suffering of these often sensitive, non-traditional male figures, while female

characters more often enjoy less emotionally painful treatment” (2001: 201),

and I would suggest that it is partly because masculinity is being so visibly

renegotiated in pop-cultural forms. As noted in the last chapter, “good” new

masculinity contrasts with “bad” tough-guy masculinity by being

“feminized,” passive, sensitive, weak, and emotional, and this contrast is

partly about the separation of gender and behavior in the new men.

[2] Like the young female characters, the new men are very aware of how gender is constructed but are often shown repressing their “real” masculinity (perhaps a recognition of powerful social conditioning). In this way, the new men’s identities are shown to be unstable rather than fixed since they too work hard to construct and reconstruct postfeminist gendered identities. In line with the show’s heteronormativity, these male characters are depicted as nonhomosocial and were identified early on as heterosexual. Victoria Robinson notes that “[t]he hegemonic model of masculinity” is heterosexual and that many (male) writers on gender both “problematize masculinity and recognize the social constructed nature of male heterosexuality” (1996: 119, 113), highlighting the contradiction here. In addition to Oz, Giles, and Xander, this chapter will use less central characters such as Owen, Ford, Parker, Ben, and Principal Wood to discuss the representation of new masculinity. The contradictions and ambivalences inherent in these characters demonstrate that what Buffy’s new men represent is not a successful new masculinity but a detailed portrait of the many anxieties surrounding binary constructions of gender.

[3] Bill Clinton was elected president in 1992 after presenting himself as “the grandson of a working woman, the son of a single mother, the husband of a working wife” and telling voters, “I have learned that building up women does not diminish men” (in Woloch 2000: 591). This points to the ways feminism has caused changes in the presentation of masculinity, and here I examine three apparently sensitive males who are presented as potential partners for Buffy but prove to be unsuitable because they cling to more traditional masculinities.

[4] The first, Owen Thurman, is introduced in “Never Kill a Boy on the First Date” (1005) as “sensitive yet manly,” and he shares some characteristics with Angel (“He hardly talks to anyone. He’s solitary, mysterious. He can brood for forty minutes straight,” says Willow). Owen’s “manly” credentials are established both by Cordelia’s pursuit of him and his rejection of her, while his sensitivity is established by his admiration of Emily Dickinson’s poetry.1 Further, Owen finds “most girls pretty frivolous” and tells Buffy there are “more important things in life than dating,” perhaps indicating that he rejects heterosexual romance, and certainly coding him as different from the typical testosterone-charged male teen. When Angel comes to The Bronze to discuss the latest crisis and discovers that the Slayer is “on a date,” Owen and Angel face off—the first in a long line of such confrontations for Buffy’s potential partners. Although Buffy confesses that she “almost feels like a girl” with Owen (a gendered articulation of how romance exposes her “split personality”), her Slayer duties inevitably intrude. She leaves Owen at The Bronze but, unhappy in a passive role, he follows the Scoobies and attempts to “protect” Buffy from a vampire. This assertion of traditional male heroism is punctured by his lack of awareness and being promptly knocked out but the definitive undermining of Owen comes in the final act. The next day he asks Buffy when he can see her again, saying, “Last night was incredible, I never thought nearly getting killed would make me feel so alive!” and Buffy confesses to Giles, “He wants to be Dangerman. . . . Two days in my world and Owen really would get himself killed.” Buffy is compelled to reject Owen because he displays “masculine” aggression, getting off on the danger of slaying (like Riley and some of the other tough guys) and because he refuses to “be careful” (in contrast with the other Scoobies).

[5] Another potential new man is Billy Fordham (Ford) from “Lie to Me.” Ford’s sensitivity is based on his closeness to Buffy: they went to school together in L.A., and he tells the gang that he is now enrolling at Sunnydale High because his father has relocated. This gives Buffy the chance to nostalgically invoke a shared past, as Willow and Xander often do. Ford suggests cheering Buffy up with “a box of Oreos dunked in apple juice but maybe she’s over that phase,” and their bond is highlighted by his nickname for her (“Summers”). Ford’s manly attractions are also clear (Xander complains, “Jeez, doesn’t she know any fat guys?”), Buffy admits that Ford was her “giant fifth grade crush,” and shots frame Buffy and Ford close together (she often holds his arm when they are walking). When Ford tells Buffy, “You can’t touch me, Summers, I know all your darkest secrets,” this seems to indicate that his intimacy has limits—he cannot know about her other life. Yet shortly afterward he is with Buffy when she rescues someone from a vamp attack, and he tells her, “You don’t have to lie. . . . I know you’re the Slayer.” Ford’s sensitivity thus extends to knowing and accepting Buffy’s other role (and her power), and even participating in some of the action, without the fear or excitement that Owen displayed.

[6] This perfect playing of the old friend/new man is punctured when subsequent scenes reveal that Ford is a member of a vampire wannabe club and show him bargaining with Spike and Dru to become a vampire, offering them the Slayer in exchange. He is simply a selfish individualist. It also becomes clear that Ford is willing to sacrifice the other “true believers” to get what he wants. That Ford is terminally ill problematizes things: he offers it as an “excuse” or justification of his behavior. Throughout his conversation with Buffy his face is in shadow, while Buffy’s is in light, polarizing them even as their discussion raises doubts about clear-cut morality. Giles’ frequently quoted closing speech in response to Buffy’s request, “Lie to me,” begins to break down certainties about good and evil in Buffy: “Yes, it’s terribly simple. The good guys are always stalwart and true, the bad guys are easily distinguished by their pointy horns or black hats, and we always defeat them and save the day. No one ever dies and everybody lives happily ever after.” The presentation of a villain invested in fantasy foreshadows the character of Warren, the male character most anxious about projecting a tough-guy image, and Ford similarly demonstrates the “badness” and violence of old masculinity.

[7] The next apparently new man is presented more simply because he only features in the “real world” of Sunnydale and knows nothing about vampires or Slayers. In her first weeks as a freshman at U. C. Sunnydale, Buffy meets Parker Abrams in the lunch queue (“Living Conditions” 4002). Later in the same episode Parker pops round to Buffy’s dorm room, and by the next episode Buffy and Parker have spent “all week” together. Parker makes several emotive speeches, demonstrating his willingness to admit and articulate his feelings. He tells Buffy that his father died recently and that this brush with mortality has changed his outlook; he is now more interested in “living for now.” Naturally, Buffy can relate to this, and Parker tells her very seriously, “It’s cool to find someone else who understands.” Parker maintains that history is really about “regular people trying to make choices” (keying in to the language of contemporary individualism and popular postfeminism) and when the two finally kiss, the concerned “new man” asks Buffy, “Is this OK? Because I can stop if you wanted, it’s your choice.” Buffy makes her “choice,” and she and Parker end up having sex (“The Harsh Light of Day”).

[8] The encounter now replays what happened when Buffy had sex with Angel but without the allegory. Her time with Parker is loaded with reminders of Angel, from Parker’s remark about “dark and brooding” guys to Spike’s explicit comment, “Guess you’re not worth a second go” (“Seems like someone told me as much. Who was that? Oh yeah, Angel”). The two worlds of Buffy conflict in a montage of Buffy pursuing her Slayer duties and checking her messages to find that Parker has not called, while the melancholy soundtrack contrasts the previous upbeat music of their developing intimacy. Eventually Buffy catches up with Parker as he talks with another female student and in this scene she seems uncertain and girlish, the freshman Buffy (“feminine”) rather than the strong, independent Slayer (“feminist”). When she asks if she did “something wrong,” he replies, “Something wrong? No, of course not. It was fun. Didn’t you have fun?” before brushing her off. As in “Family,” Spike offers a “feminist” explanation, albeit couched in rather unfeminist language: “Did he play the sensitive lad and get you to seduce him? Good trick if the girl’s thick enough to buy it.” “Playing the sensitive lad” is a strategy that Parker adopts in order to make his conventionally masculine conquests. The success of this strategy relies on traditional moral and sexual values: if the girl thinks she seduced him, then she is likely to blame herself, as indeed Buffy does.

[9] Buffy’s rejection by Parker is shown again in succeeding episodes, and during “Fear, Itself” Buffy tells her mother: “I’m starting to feel like there’s a pattern here. Open your heart to someone and he bails on you.” In “Beer Bad,” Buffy daydreams about saving Parker from a vamp attack. That this daydream occurs in a lecture on the pleasure principle while Parker is chatting up yet another female student is not lost on the viewer. Willow persists in dissuading Buffy: “He’s no good. There are men, better men, where the mind is better than the penis,” highlighting the changing priorities of postfeminist young women. Riley, Buffy’s future boyfriend, disapprovingly tells Buffy that Parker “sets ’em up and knocks ’em down,” and when Willow goes to confront Parker, he attempts to charm her too. This time his performance of “the sensitive lad” is deflated by Willow’s awareness: “Just how gullible do you think I am? I mean, with your gentle eyes and your shy smile and your ability to talk openly.”

[10] Meanwhile Buffy and some other college students have regressed into Neanderthals and a fire has started, trapping Willow, Parker, and several others. As in her fantasy, Buffy saves Parker from mortal danger, and a pensive piano plays in the background as he tells her, “I’m sorry for how I treated you before, it was wrong of me.” This fantasy of romance is undercut when Cave-Buffy merely whacks him with her improvised club, leaving the other Scoobies to look down on him, the camera giving a low shot from Parker’s prone body.2 Viewers here get the satisfaction of Parker being rejected through a device that frees Buffy from her contradictory “feminine” and “feminist” positions on romance and sexual behavior. Parker is finally dismissed by Riley when Parker tells Forrest that Buffy is “kinda whiny” and “clingy,” concluding with a crack about “freshman girls” and “toilet seats.” Riley punches him out, apparently establishing his own credentials as a “sensitive lad” (“The Initiative”).

Scott

[11] Scott Hope has a brief relationship with Buffy in season 3, but this is complicated by Buffy’s Slayer duties and Angel’s return from hell, and Scott is not entirely discredited as a new man. Much later the ex–Sunnydale High vampire Webs (Holden Webster) tells Buffy that Scott said she was gay and continues, “He says that about every girl he breaks up with. And then, last year, big surprise, he comes out” (“Conversations with Dead People”). This is the only instance in Buffy where sensitivity and (homo)sexuality are related, possibly resolving the complicity between heterosexuality and patriarchy. Yet Scott himself does not reappear. All of these failed partners contribute to undercutting the myth of romance in Buffy and highlight romance relationships as the one area in which changes to masculinity are needed and looked for.

[12] Oz is figured primarily as the love interest of one of the main characters (generally a female role) and was seen by some viewers as a successful paradigm of new masculinity, combining both “masculine” and “feminine” characteristics. Oz is often identified by his role as rock guitarist and is described by The Watcher’s Guide Volume 2 as “the definition of cool and composed” (Holder, Mariotte, and Hart 2000: 69), two major factors in his appeal. In one way his habitual silence is part of this cool composure and can be read as a trait of “old masculinity” (the strong silent type), yet simultaneously it can be identified as a passive “feminine” characteristic. From the beginning Oz was presented as sensitive and thoughtful, refusing to allow his relationship with Willow to develop before they were both ready (in contrast to Parker’s pretence). Kristine Sutherland, who plays Joyce Summers, remarks on the attractions of this: “It was the scene in the van where she asks him to kiss her and he says, ‘I don’t want to kiss you until you want to kiss me.’ That is the kind of man that every woman is looking for” (in Golden and Holder 1998: 215). Once again a new man is one who appears be sensitive to young women’s anxieties about relationships. The connection between Oz’s wolf cycle and the female menstrual cycle is explicitly referred to in “Phases” and further feminizes Oz. Oz also proves that it is possible to be both a nerd and, as Xander puts it, “more or less cool” (“The Zeppo”), or that social success need not be dependent on particular versions of masculinity. Of all the primary male characters in Buffy, only Oz is a dissimilar physical type and an atypical male lead in that he is short and slightly built. (Willow’s next partner, Tara, is also an atypical lead.) This allows the show to present variants of masculinity even in appearance.

[13] On the whole Oz appears “very much at ease with his masculinity” (Simkin2004b: 5) and seems adaptable and free of the anxieties that plague other characters. Oz is willing to stand in for best friend Willow when the Scoobies are worried about Buffy in “Living Conditions.” “If it wasn’t for this English paper, I’d be right there, listening, doing the girlie best friend thing,” Willow worries. “I can do that,” responds Oz, going on, “Well, I’m not saying we’ll braid each other’s hair, probably, but yeah, I can hang with her.” Yet his characteristic stoicism can cause problems, and at times friction in his relationship with Willow is exposed. In “Earshot,” when Buffy can read thoughts, Willow panics because Buffy knows what Oz is thinking and Willow believes their intimacy will never stretch that far. Another exchange seems to suggest tension when Oz expresses the hope that Buffy has not been encouraging Willow to practice magic (“Fear, Itself”). By the end of a three-way exchange between Buffy, Oz, and Willow, Oz emerges as “supportive boyfriend guy,” his reluctance dispelled as concern for Willow’s safety. “Just know that whatever you decide, I’ll back your play,” he concludes, leaving Buffy and Willow to marvel over his “sweet” nature.

[14] Episodes focusing on Oz tend to be either about his relationship with Willow or about the werewolf. In “Fear Itself” he tells Willow and Buffy, “I know what it’s like to have a power you can’t control and every time I start to wolf out I touch something—deep, dark. It’s not fun.” Later in the episode this fear is played out in the Halloween “haunted house” when he starts to wolf out for no apparent reason. Oz leaves Willow (to “protect” her) and huddles in an empty bathtub telling himself, “You’re not going to change.” Thus although Simkin suggests that Oz does not suffer from the anxieties about masculinity that other male characters display (2004b), I argue that Oz’s anxiety about the wolf is his anxiety about masculinity. Carolyn Korsmeyer notes that Wolf-Oz demonstrates “anger and aggression as brutish elements of the emotional range” and concludes that this “seems especially apt for the male of the species” (2003: 164). Oz’s sensitivity is proved by his realization that he needs to restrain this side of himself.

[15] It is no coincidence that his crisis concerns another young woman, Veruca, who comes between Oz and Willow because she too is a werewolf and a musician (“Wild at Heart”). Veruca disturbs Oz’s peaceful surface: “You’re the wolf all the time, and your human face is just your disguise. Ever think of that?” Veruca’s animal/sexual magnetism seems to affect other men (both Xander and Giles are riveted by her stage presence), and physical/sexual desire is highlighted in her liaison with Oz, so that despite the “cuddly” nature of his relationship with Willow he is sexualized. Dyer observes that white sexuality is often seen as “bestial and antithetical to civilization” (1997: 26), and Oz as werewolf literalizes this view. Challenged by Willow, he maintains, “I don’t know what Veruca and I have done. When I change, it’s like I’m gone and the wolf takes over,” but Willow points out, “You wanted her. Like, in an animal way.” Significantly, Veruca, not Oz, carries most of the blame for their sexual transgression (and Willow describes Veruca as dressing “like Faith,” another sexualized bad girl). Following Veruca’s death, Oz leaves Sunnydale to try and control the werewolf. As mentioned in chapter 2, he is an aggressive intruder when he returns to Sunnydale and disrupts Willow’s new relationship with Tara, sexual jealousy calling out the wolf he thought he had tamed. After escaping the Initiative, he again leaves Sunnydale, Willow, and the series, establishing a pattern in his behavior.3

[16] Robinson identifies an “ambiguity around male sexuality,” noting that seeing it as “simultaneously both vulnerable and powerful” is necessary to changing definitions of masculinity (1996: 115). Oz in particular exemplifies this ambiguity. External factors (actor Seth Green’s other commitments) meant that Oz lasted only around two seasons as a Buffy regular, but the manner of his departure underlines the tension between competing versions of masculinity. All the Scoobies are presented as flawed in some way, but many male characters’ flaws or mistakes are related to gendering or gendered behavior. Although Simkin suggests that Oz’s departure “offers only a puzzlingly abrupt, incongruous and unsatisfactory resolution” (2004b: 7), I am more inclined to agree with Mendlesohn, who argues that it signals a reluctance to allow Willow agency (2002: 55)—something I see as fitting an overall tendency. Sayer’s observation that “[o]ver the course of the show it is primarily the men (Angel, Oz, Riley and to some extent Spike) who have left” (2001: 112), together with Buffy’s comment on men “bailing,” point to the frequency of men leaving women. All of the characters Sayer picks out demonstrate a contested masculinity, and I argue that their leaving undermines their apparent sensitivity, highlighting the tension within them.

[17] Another important male character, Giles, was early described as “a decidedly feminized male” (Owen 1999: 24). As an adult, Giles is exceptional: in a show where almost all adults and authority figures are proved “bad,” he is not only fully aware of the teen characters’ heroism, but supportive of it. This is largely because, as Christine Jarvis has noted, Giles begins as the school librarian and honorary teacher, and “where good teachers are portrayed in popular culture, they usually stand against the system” (2001: 264). Giles stands out against the system of school and of hierarchy. In terms of age, and origin (he is British), Giles is presented as different. Yet he shares certain characteristics with other new men.

[18] Giles’ new-man sensitivity may be difficult to pinpoint, since he is presented as a reserved character and since age separates him from the teens. Although vampires like Angel are effectively older than Giles, he is generally seen as the oldest character in the team, highlighted by his traditional dress and speech (also related to his British-ness). Even in the early seasons, however, when he is at his most tweedy, Giles (and the show) is aware of this. When Jenny Calendar asks him, “Did anyone ever tell you you’re kind of a fuddy duddy?” he responds, “No one ever seems to tell me anything else” (“The Dark Age” 2008). The fact that he has two “first” names (Rupert Giles) allows him to be regularly called “Giles” by the teen characters, without this ever sounding strange (as it might if they called him “Smith”), and suggesting a degree of intimacy while not quite putting them on the same footing. Giles’ position as the only adult in the group offers a different perspective to the viewer but still allows his emotional side to be revealed in a number of ways. First, and perhaps most obviously, his emotions are shown in his fathering of Buffy, as discussed in chapter 7. But he also demonstrates a keen sense of responsibility for the safety of the other teens and displays emotion and affection when they are threatened (as when they think Willow has been killed and turned into a vampire in “Doppelgangland”).

[19] Giles takes his responsibility as part of the team very seriously. When Willow asks him, “How is it you always know this stuff? You always know what’s going on. I never know what’s going on,” Giles replies, “Well, you weren’t here from midnight to six researching it” (“Angel”). Giles is always a key member of the Scoobies and their communal efforts. He is presented as hetero- rather than homosocial, and his few adult friendships or affinities are with both males and females (Angel, Ethan Rayne, Jenny Calendar, Joyce Summers, Olivia). After the school is destroyed and he loses his job as librarian, Giles is allowed to shed his reserve, and the teens unexpectedly find common ground with him. His position in the team is reinforced as he also “grows up,” briefly acquiring a British girlfriend, Olivia, and doing his own thing. He is never set up as the leader, though his knowledge and experience are often useful and are respected by the others. His role as Buffy’s Watcher (trainer and researcher, as well as mentor) means that Giles is inevitably a passive rather than an active character. Despite his “generic roots . . . in the von Helsings [sic] of British horror” (Whedon in Lavery 2002a: 50), like Xander, Giles is rarely involved in the physical aspects of slaying. But this does not negate his heroism. In “The Zeppo” he is a key player in the mostly off-screen attempt to avert another apocalypse, and when Buffy says, “It was the bravest thing I’ve ever seen,” Giles merely responds, “The stupidest.” In this way, Giles’ heroism is presented as team effort and self-sacrifice rather than “masculine” individualist heroics.

[20] Giles also allows the teen Scoobies independence and agency. His positions of authority (as Watcher and as a kind of teacher) are traditional patriarchal roles and encourage him to try and take charge early on, but this is resisted by Buffy and the others. J. P. Williams has argued that Buffy’s “knowledge of Slayers and slaying is filtered through” Giles, “who, in his dual roles of Watcher and librarian, controls Buffy’s access to knowledge and parcels out information on a ‘need-to-know’ basis” (2002: 62). I would point out that although it is rarely articulated, the show demonstrates that a Watcher must learn as much as a Slayer, since s/he has only theory and no practice. That Giles lacks practical authority is shown in Buffy’s frequent insubordination, and he supports her rejection of the Council. Buffy’s relationship with Giles can be problematic, but generally Giles allows female characters active agency. Ms. Calendar takes the lead in their romance, and Giles generally encourages both Buffy and Willow to develop their particular skills and rarely implies that they are not strong enough to face potential challenges.

[21] Thus Giles seems to fit the profile for a new man. Yet Giles’ position as adult makes him initially the only member of the Scoobies to work, and he is a protector and provider. This role as provider places others in a dependent position, though this is never spelled out. Giles provides transport and, more important, space: three of the four Scooby meeting places are “his” (the library in early seasons, his home in season 4, and The Magic Box in seasons 5 and 6). That Giles’ identity crisis in season 4 focuses on his decline to useless, unemployed drunk (part of the larger disintegration of the Scooby Gang in this season) merely highlights how his identity is tied up with wage earning and providing. The male character Giles has most in common with in early seasons is Angel (also an older male, a displaced European, well traveled and well read), and the two meet often over their concern to protect Buffy. As season 5 develops, Giles acts as protector of Dawn and Buffy and provides financial support when they are in difficulty. (Since viewers know Buffy managed to get Giles reinstated as a Watcher with full back pay in “Checkpoint,” it might not be such an invidious position. It is also clearly designed to show Buffy’s inexperience in the “real” world and her need to rely on someone else.)

[22] Giles displays other traditionally masculine characteristics—aggressive sexuality and physical violence—though these are often displaced onto his alter ego, Ripper. Ripper is constructed deliberately to contrast the traditional Giles of early seasons,4 demonstrating the binary nature of masculinity in Buffy and the split personality of many characters. He thus offers similar viewing pleasure to the alternative versions of Willow. In “The Dark Age” viewers and characters discover Giles’ past as a university dropout who dabbled in dark magic. Ripper is first hinted at when Buffy discovers Giles at home, neglecting his Watcher responsibilities and apparently drunk. She reports that he was acting “very anti-Giles” and Xander observes, “Nobody can be wound as straight and narrow as Giles without a dark side erupting” (foreshadowing similar comments on Willow and Buffy). Although the Ripper aspect of Giles is more aggressive and assertive (telling Buffy, “Hey, this is not your battle and as your Watcher I am telling you unequivocally to stay out of it”), he remains feminized. “You’re like a woman, Ripper,” the demon Eyghon tells him, wearing Ms. Calendar’s body. “You never had the strength for me.”

[23] Ripper surfaces at subsequent points, most notably in “Band Candy” (3006), and is always associated with aggression and violence (I see him as a strategy for the use of violence in an otherwise intellectual character). In general the violence of Ripper is used by Giles as part of his role in protecting Buffy and the Scoobies. His language, like Giles’, signals his difference, but it also signals a difference from Giles: the received pronunciation of the privileged and educated Brit is replaced in Ripper by a (rather exaggerated) generic southern English working-class “accent.” I would argue, therefore, that along with Jack O’Toole and Spike, Ripper links a certain type of masculinity with certain types of men: middle-class men may be new men, but working-class men are real men. It is also suggestive that some business with Giles’ glasses often heralds the return of Ripper, and Ripper does not wear glasses, a classic signifier of the wimpy swot. His costuming in “Band Candy” associates him with either a working-class hero (like early Marlon Brando) or, perhaps, a middle-class would-be rebel like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). This visual presentation of Ripper as a 1950s rebel does not match his actual rebellion in the 1970s, but it does draw on intertexts that are classic representations of masculinity and a period of American cultural history much concerned with asserting masculinity in the face of feminization (books from the 1940s like Philip Wylie’s Generation of Vipers and Edward Strecker’s Their Mother’s Sons influenced this view).

[24] Ripper first appears in an episode where Giles’ relationship with Ms. Calendar is about to become sexual, though his violence is not directly related to or triggered by sexuality in the narrative (as with Oz and Angel/us, for example). Giles’ position as a forty-something who hangs out with a group of teenagers could be slightly dubious, as Buffy points out: “So, you like to party with the students? Isn’t that kind of skanky?” (“Welcome to the Hellmouth”). Initially, Giles’ role as nurturer defuses any sexual attraction (within the narrative), and age divides him from Buffy and her peers, even when the teen characters themselves become adults (see also Levine and Schneider 2003: 308). Outside the narrative, Anthony Head, the actor who plays Giles, “was surprised by the strong reaction to Giles as a sex symbol” (Golden and Holder 1998: 210), though he had played the romantic lead in a series of successful coffee adverts, and this “sexy” image is subsequently played up.5 Indeed, Ms. Calendar’s follow-up to her “fuddy duddy” remark was “Has anybody ever told you’re kind of a sexy fuddy duddy?” Part of Giles’ loosening up in season 4 is about acquiring a kind of “cool,” as when the Scoobies witness his “gig” at the coffee shop and Willow admits that she had a crush on him (“Where the Wild Things Are”). Given the perhaps unexpectedly broad demographic of Buffy’s audience, Giles offers viewing pleasure to female and male viewers of the show, in a similar way to characters like Inspector Morse (see Thomas).

[25] Giles’ relationships with Jenny Calendar, and later Olivia, work in several ways: to establish him as heterosexual, to remove him from sexual connections with teen characters, and to further emphasize his age difference (the teens generally see it as “gross” and inappropriate that older people have a sex life). They also show that he is sexually attractive. Ripper has sex with Joyce in “Band Candy,” and when Buffy can read thoughts in “Earshot,” she overhears her mother thinking that Ripper was like a “stevedore” during sex (another reference potentially relating class and sexuality). Edwards also suggests that Giles’ sexual prowess is “proved” by his black girlfriend, Olivia (2002: 95)—he can satisfy an “exotic” lover. (Furthermore, it could be argued that this interracial relationship links new masculinity with liberal values.)6 Although Giles is characterized primarily as a new man, he is far from weak and effeminate—he is a desirable heterosexual partner. Again Buffy has the best of both worlds. Matching the apparently contradictory combination of “femininity” and “feminism” in the young female protagonists, Giles is both a sensitive new man and a virile lover whose heterosexuality upholds rather than challenges patriarchal structures and gendering.

[26] Dyer argues that the “divided nature of white masculinity. . . . is expressed in relation not only to sexuality but also to anything that can be characterized as low, dark and irredeemably corporeal” (1997: 28). I would suggest that Ripper’s other more traditional masculine qualities such as aggression and physical violence are corporeal (physical) and presented as uncharacteristically “low” or “dark.” These emerge at other times, as in the season 4 chainsaw-wielding scene (“Fear, Itself”). Being turned into a Faryl demon (“A New Man”—the title is open to all kinds of interpretations) seemed to imply the return of the dark side for Giles, and this episode features Ethan Rayne, an acquaintance from Giles’ Ripper days and a recurring villain. The episode highlights Giles’ sense that he is losing his role in the group when Professor Walsh undermines his special relationship as a father figure and mentor to Buffy. This is partially resolved by the fact that Buffy later recognizes Giles within the demon, yet demon-Giles is shown deliberately scaring Professor Walsh, whom he called a “harridan.” Here the show articulates debates about changing masculinity, encouraging a “feminist” explanation of Giles’ behavior. Walsh clearly evokes anxieties about Giles’ masculinity, verbalised in the company of a male friend and while engaging in the “masculine” pursuit of drowning his sorrows. “Twenty years I’ve been fighting demons,” Giles slurs to Ethan, “Maggie Walsh and her nancy ninja boys come and six months later the demons are pissing themselves with fear. They never even noticed me.” He continues, more explicitly, “She said I was an absent male role model. Absent my arse, I’m twice the man she is [my emphasis].” Like the tough guys, Giles uses language to preserve gender distinctions and to shore up his own masculinity.

[27] At the episode’s conclusion Buffy tells Riley that she does not want to speculate on what might have happened if demon-Giles had killed Ethan. She means largely that they might not have been able to turn Giles back, but bear in mind the cardinal sin on Buffy is to kill a human. This potential violence is always within Giles, though arguably the comic aspects of Giles’ transformation here work against a serious view of his behavior. As the pressure to defeat Glory heightens in season 5 and Buffy insists on protecting Dawn at the possible expense of ending the world, Ripper begins to reemerge. In one episode Giles threatens Spike with such vigor that the vampire is for once left speechless (“I Was Made to Love You”), then Giles wreaks unspecified off-screen violence on one of Glory’s demon minions in order to get information (“Tough Love”). In the showdown Buffy defeats Glory, who withdraws, leaving Ben, her human host, battered but intact. Buffy makes Ben promise that he/Glory will never again pursue her and Dawn, then lets him live. Giles, however, suffocates Ben, explaining that Buffy “couldn’t take a human life. She’s a hero, you see. She’s not like us” (“The Gift”). Thus the apparently civilized Giles will kill a human when he believes that it is morally justified. Giles’ statement also sets up oppositions (“she” and “us”; his use of “hero” might imply “villain”). Certainly his use of violence to protect the female Buffy allows him to take on a conventional masculine role as her protector, and Jacob M. Held even describes Giles as the only one “strong enough” to kill Ben (2003: 237). As I argued in chapter 1, Giles’ killing of Ben allows Buffy to preserve her moral purity.

[28] During seasons 6 and 7 Giles is absent for much of the time and generally reverts back to a father figure.7 I have already mentioned that Giles clashes with Buffy over Spike (as with his killing of Ben, he sees this as being for the greater good) and she rejects his advice. Later in “Chosen,” however, he supports Buffy’s “radical” final solution (“it’s bloody brilliant!”) and joins the original Scoobies for the last battle. Giles displays some potential as a new man, but his negotiation of gender and gendered relationships is often complicated by his role as a parent figure, as I have indicated. Not until Principal Wood does the show offer a further, more mature version of a new man, this time uncomplicated by parental anxieties. I discuss Wood at the end of this chapter.

[29] “Gentle Ben,” as Glory calls him, implying another “sensitive lad,” is a hospital intern who features in season 5. He takes an interest in Buffy and her mother’s illness while they are at the hospital. This positions him in a caring profession sometimes associated with women, and he is contrasted with the older male doctor who is presented as a distant professional. He looks after Dawn at various points, further reinforcing his “feminine” nurturing qualities, though his heterosexuality is established by his interest in Buffy. He might even have been a partner for her, but she puts off a date with him after her encounter with Warren and April (“I Was Made to Love You”). Ben is trusted enough to help the Scoobies when Giles is seriously injured as the gang try to escape Glory and the Knights of Byzantium at the end of the season. He betrays them because Glory inhabits his body and takes over at inappropriate times. Ben is thus further feminized, especially by sudden reappearances (from Glory) when he ends up wearing dresses as in “Spiral” (notably, this does not masculinize Glory). Dawn sums up Ben’s nature when, abducted as the Key, she tells him that she prefers Glory because she does not pretend to be anything other than a monster (“The Weight of the World”), implying that Ben too is only “playing” the new man.

[30] Xander demonstrates characteristics of a new man, though at times the implication is that he is a new man because he cannot be a real man. Xander’s emotional ties to the group are obvious: his long-lasting friendship with Willow is a core element and his position as the “heart” of the group is emphasized more than once. It is his bond with Willow that saves the world at the end of season 6: despite Dark Willow’s sarcastic remark “You’re going to stop me by telling me you love me,” this is almost exactly what happens. Xander tries to reconcile Buffy and Riley when their relationship becomes distant. He refuses to be caught between Willow and Anya when they vie for his attention, and again his loyalty is proved when he refuses to choose one of “his women” to die at the hands of a troll in “Triangle” (5011). That Xander represents emotion, love, and friendship is part of the project of dissociating gender and behavior: more conventionally the “heart” of the Scooby family would be female. In this way Xander demonstrates typically “feminine” competencies in relationship management (though his romance relationships threaten to disrupt the Scooby family) and a willingness to articulate emotion.

[31] Xander is eager to play a part in the communal efforts of the Scoobies, even if his role tends to be passive and he often has to be rescued by Buffy. He is not physically up to fighting evil, and though keen, he is most often knocked out or incapacitated. Indeed, his high point in fight scenes is the slow-motion slap-fight with Vamp Harmony in “The Initiative” (mentioned in chapter 3). In a less exaggerated but similar way to hapless male “hero” Joxer from Xena: Warrior Princess, Xander’s lack of physical prowess affords pleasure to the viewer through role reversal (the opposite of Buffy’s strength and action). Despite this apparent lack of “real masculinity,” the show makes much of Xander as a soldier, first in “Halloween” when he “becomes” his soldier costume, and later in episodes relating to this. This may simply be a useful plot point, but it also asserts some “real” masculinity in Xander, and Buttsworth suggests that his transformation invokes “the ways in which the military claims to ‘make men out of boys’ ” (2002: 187). Xander initially wants to be a hero, and developments like “The Zeppo” mean that by season 4 he is comfortable telling Buffy, “You’re my hero” (“The Freshman” 4001). Notably Xander’s version of heroism, like Giles’, involves self-sacrifice and a willingness to put others before himself, as well as personal risk, demonstrated in his face-off with Dark Willow (Wendy Love Anderson [2003: 226] points out the potential religious allegory in this scene). This self-sacrifice is further underlined in the fight with Caleb in season 7, where Xander is seriously wounded in the eye (“Dirty Girls”). Relating gendering to Christianity, Dyer suggests that suffering is almost an assertion of white masculinity (1997: 17).

[32] Like Giles and Oz, Xander is primarily heterosocial; at high school he seems to avoid the company of other males. He gets along with girls and is accepted by them as an unthreatening, equal companion: “You’re not like other guys at all,” Buffy tells him. “You’re totally one of the girls” (“The Witch” 1003). In the second ever episode he says, “I’m inadequate, that’s fine. I’m less than a man” (“The Harvest”). Much of Xander’s appeal in early seasons was based on the fact that he is very conscious of being “less than a man,” part of what Simkin calls “his endearingly self-deprecating nature” (2004b: 18). When Xander is discovered as a crasher at a frat party, he is forced to dress as a woman and is ridiculed for his lack of “real” masculinity (“Reptile Boy”). Later Anya is attracted to him because he’s “not quite as obnoxious as most of the alpha males” (“The Prom”). Thus I would agree with A. Susan Owen that Xander consistently “makes ironic and self-mocking commentary on the perils and challenges of masculine social scripts” (1999: 26), offering a variant of masculinity and perhaps eliciting recognition from the viewer. Simkin argues that Xander “does not fall into the same category as Jonathan, Andrew and Warren” (2004b: 11), but the comparison with the Trio does much to clarify Xander’s sense of inadequacy: the way he deals with it differs radically from the way they do. All this may seem to prove that Xander’s character is a new representation of masculinity, one that complements the show’s strong female protagonists.

[33] Yet Xander is far from the perfect new man. Like Giles, he eventually has paid employment, making him a wage earner and provider. His job in construction establishes a traditional kind of masculinity related to physical work, akin to an earlier American ideal that Michael Kimmel calls “the Heroic Artisan” (1997: 16). This relates to Xander’s uncertain class positioning: he is the only teen character in early seasons who is not clearly middle class. In season 3 his brief liaison with Faith ties him to another character who is differentiated in class terms, and I suggested in the last chapter that one of the less obvious undercurrents of “The Zeppo” is that Xander rejects tough-guy masculinity because he is trying to escape the working-class identity represented by Jack and his gang. Similarly, in season 4 Xander’s series of minimum-wage jobs and perhaps even the unfounded rumor that he might join the army imply a future as a working-class nobody. His success in the construction industry establishes him in a working-class “trade” (rather than a middle-class “profession”), but his rapid rise through the ranks shows him moving toward middle-class managerial status. “Lessons” cuts from Giles telling Willow that “we all are who we are, no matter how much we may appear to have changed” to Xander emerging from an apparently new car, wearing a suit and tie. As a kind of self-made man, Xander is another example of shifting identity. He becomes a provider, highlighted through his relationship with Anya, as discussed in chapter 1, and season 7 shows Xander acting as “man of the house” for the Summers women. Initially he wished to be a protector, and now he is cast in this role, though not quite in the heroic way he imagined. Xander is often called upon to protect Dawn, and in the final battle Buffy sends him away to do just that, telling him, “I need someone I can count on, no matter what happens” (“End of Days”). Notably, Dawn asserts her independence and sabotages the plan: Xander is “not man enough” to stop her.

[34] But as I see it the real problem with Xander’s representation as a new man is sexuality, especially given the contradiction already outlined between new masculinities and heterosexuality’s complicity in patriarchal structures. Sexual prowess is again called on to demonstrate that a new man is in fact a real man. Xander’s uninhibited (hetero)sexuality can be read as another trait attributed to the working class by the middle class. Early on he appeared to be sexually innocent, if eager for experience. Xander’s unrequited love for Buffy is emphasized in season 1 by his transformation in “The Pack,” when, possessed by the spirit of a hyena, he attempts to force himself on her. Giles comments, “Testosterone is a great equalizer. It turns all men into morons,” but it is made clear that Xander is only acting this way because of the spirit possession and therefore that he is not a typical adolescent male. This sexual naïveté is highlighted again in season 3, when he has a one-nighter with Faith (“Consequences”). Despite complaining about having “bounced back to being a dateless nerd” in “Beneath You,” Xander’s relationships with Cordelia and Anya and Willow’s long-unrequited love for him prove his desirability. Whedon’s admission that Nicholas Brendon (who plays Xander) is “way too hunky” to be a nerd (in Lavery 2002a: 38) underlines this as potentially another source of viewing pleasure, and the show played it up with the “Speedo moment” of “Go Fish” (2020). All of Xander’s relationships are based on physical attraction (Cordelia, Faith, Anya), and he finds them problematic.

[35] Xander’s romances and sexual liaisons almost seem designed to “make up for” his other shortcomings. Early on his fascination with sex was seen as an integral part of his geek teen boy behavior: “I’m seventeen. Looking at linoleum makes me wanna have sex” (“Innocence”). Xander’s (and the show’s) self-awareness thus asserts his typical behavior and his difference. Anya’s insistence on discussing their sex life in public has been highlighted as part of her characteristic difference, but it serves another function as well. That Xander is a “Viking in the sack” (“The Yoko Factor”) adds a twist to his apparently new masculinity: just as Giles is able to “satisfy” a black woman, Xander is able to satisfy an ex-demon. Like Giles, Xander is not just desirable—he is virile. And despite the many subtexts of Buffy, Larry’s assumption that Xander is gay, and some of Xander’s own more unguarded comments (particularly about Spike), Xander’s liaisons have always been firmly heterosexual. So much so that his “Willow, gay me up” speech in “First Date” is clearly a joke stemming from his disgust at attracting more “demon women.” Saxey suggests that fan fiction often presents Xander as gay because his “problems as they are currently presented—worries about his role in life, struggles with his notions of masculinity, sex and relationships—don’t contain within them a recognizable solution” (2001: 202). That is, fans see heterosexuality, consciously or not, as a stumbling block to reconciling the “problems” in constructing contemporary masculinity. To Xander his relationship with Anya is a strong affirmation of his masculinity, and Simkin notes that the “real crisis [in “The Replacement”], however, is centred on Anya” (2004b: 21). “You make me feel like I’ve never felt before in my life,” he tells her, “like a man” (“Into the Woods,” my emphasis), and before the showdown at the end of season 5, Xander asks Anya to marry him. Xander’s high school fantasies never disappear, and even in season 7 he dreams about young innocent Potentials offering themselves to his sexual experience (“Dirty Girls”). This is presented as comical, and Xander’s function as a comic character tends to play down his flaws; they are laughable foibles that add to his character.

[36] Xander and Willow’s male-female friendship is a core element holding the gang together, but notably Xander is never shown in a nonsexualized relationship with a female character. As Korsmeyer observes, even “Xander’s steadfast friendship for Willow has an early erotic aspect” (2003: 167), and as I mentioned earlier, he is initially attracted to Buffy. In the season 2 finale, Xander chose not to tell Buffy that Willow had a chance of returning Angel’s soul, and Buffy was forced to kill Angel rather than Angelus (this is raised again in “Selfless” but not addressed). Clearly this is motivated by Xander’s jealousy of Angel, and Gregory J. Sakal notes the “hubris of his presumption to know what is best for” Buffy (2003: 246), a removal of agency from the female. Xander also told Riley about Buffy and Angel’s sexual relationship (“The Yoko Factor”). When Xander finds out that Spike and Anya consoled each other sexually after the wedding fiasco, Xander pursues Spike with an axe (“Entropy” 6018). Here sexual jealousy (of Anya and Buffy) is Xander’s downfall (the same jealousy he displayed to all potential partners for Buffy in high school): his condemnation of Anya, “I look at you and I feel sick because you have sex with that,” also includes Buffy, his “hero” and unattainable idol. (Both Sakal 2003: 248 and Levine and Schneider 2003: 306 read Xander as idealizing Buffy, as “femininity” has traditionally been idealized.) Xander’s behavior is consistently motivated by sexual jealousy—a typical “masculine” quality.

[37] Furthermore, despite his attraction to strong women (shared with almost all male characters, regardless of their gender “politics”), Xander has problems allowing his partners equality and agency. Granted, in his early relationship with Cordelia she appeared to be dominant, largely because of her higher status in the high school world, but Xander’s relationship with Anya is a key example of inequality. Xander jilts Anya at the altar after receiving a “nightmare vision” of their future together (“Hells Bells”). His vision is very similar to his version of Angel and Buffy’s future in “Surprise,”8 but Xander is now in the position he imagined for Angel, “dreaming of the glory days,” while Anya works to support their family. Xander’s feelings for Buffy are still creating tension, while the mixed heritage of their children also causes friction. Although Xander’s background here is not as ambivalent as in previous seasons (since his family are shown), domestic violence and drinking again imply working-class behavior (as noted in chapter 3, these tend to be attributed to the working class). Xander’s violence and aggression in the vision are clearly modeled on his own father (see chapter 7), but he uses his new-man sensitivity as an “excuse”: although he still appears to love Anya, he runs away, implying that this is to protect her. Once again a new man demonstrates a capacity for violence, cannot cope with the situation, denies the female partner agency, and leaves. And, as with Oz, Xander is not really blamed, in this case because Anya is still an outsider.

[38] Xander’s anxieties throughout Buffy have concerned his inability to contribute to the group with a special talent (superpower): even in season 7 he discusses this with Dawn (“Potential”). In “Checkpoint” Buffy answered this criticism from the Watcher’s Council by pointing out, “‘The boy’ has clocked more field time than any of you put together,” countering the belittlement of “the boy” with a military metaphor and underlining Xander’s willingness to contribute. I would point out in conclusion that Xander does in fact have a special status: he is, as the show underlines, the normal one. Despite his ambivalent class background and his geek status, he is a white heterosexual male and is thus the only Scooby who is also a member of the historically dominant sector of American society. Dyer notes of the character Prendergast in Falling Down (1993) that his “very unobtrusiveness . . . allows him to occupy more comfortably the position of ordinariness that is the white man’s prerogative” (1997: 221), and this is an apt description of Xander.9 This may be exactly why Xander has so many problems negotiating a new masculine identity. Although his version of masculinity is not exactly “hegemonic,” his position as white American heterosexual male allows him to “benefit without really trying, from a patriarchal dividend” (Johnson 1997: 15).

[39] In season 7 Sunnydale High School opens again, and its new principal is a departure from previous incumbents—he is young and black. Like other nonwhite characters on Buffy, Principal Robin Wood is whitewashed, assimilated: he is a middle-class professional who tells Buffy he is from Beverly Hills, not “the ’hood” (“Help” 7004). Wood is an interesting development in Buffy’s representation of race, but he is also, I would argue, the most uncompromised new man. He is the son of Nikki Wood, the subway Slayer killed by Spike in 1977 New York (“Fool for Love”). This means that Wood is from a matriarchal line; he remembers a strong mother and no father (a typical characterization of black families based on post–World War II demographics and employment patterns [Woloch 2000: 524, 582]). As Spike points out, Wood finds it hard to accept that although Spike may have taken his childhood away by killing his mother, his mother had to balance “the mission” and her responsibility to him (“Lies My Parents Told Me”).

[40] Wood is also one of very few “good” adults, and unlike most other adults on Buffy, he does not function as a parent figure (except for his role as a teacher), perhaps because he enters when the original teens are themselves adults. Furthermore, because he is Other, Wood is not implicated in white male supremacy: he accepts Buffy as an equal (though he is still her boss) and later a “general” and supports Faith as a leader. Like Xander, he has no superpowers, though he has been trained to fight vampires: “I’m just a guy. Granted, a cool and sexy vampire-fighting guy, but still” (“First Date”). In this way he offers a similar “ordinary” subject position to the viewer, though like other characters of color on Buffy he remains a minor character. His scenes do allow him some development apart from the main protagonists, as when the First appears to him as his mother, but he is primarily used to illuminate the role of Slayer and the newly souled Spike. He has little interaction with the other Scoobies; he opposes Spike, the dead white European male, and allies with Giles, the only other “man” in the group and someone also marked by difference.

[41] His vendetta against Spike is related strongly to emotional reactions,10 and his sensitivity is shown through the articulation of emotion that the show values. In connection with his mother, in his interaction with Faith (he is part of her redemption), and even in his early conversations with Buffy he is not afraid to admit to being scared (“Beneath You”) or to needing love and reinforcement. When he tells Faith how the First appeared as his mother he says he knew it wasn’t real, “but I still wanted my mother to hold me like a baby,” adding, “In a manly way, of course” (this awareness of gendered constructions further links him to other new men). His connection with Faith reinforces his presentation as a “pretty decent guy.” Furthermore, his assertion that “nobody wants to be alone” (“Touched”) proves that he is not an individualist. Wood shares the communal ethos of the group—he is willing to work beside them, even Spike, to fight evil.

[42] Like other new men Wood displays violent aggression and heightened sexuality. In his case these are “justified” by the show’s narrative and can also be related to his representation as a nonwhite character and to age (in “First Date” Xander says he must be at least ten years older than Buffy, but the show’s chronology puts him at around 30, rather young to be a high school principal). His aggression is directed at the “right” targets, and if he initially resents Spike, this is understandable given his history, and it is eventually resolved. Wood’s history allows him more subjectivity than any other character of color and sufficient emotional articulation to qualify as a new man. Like Kendra, Wood is sexualized and presented as a sexual object rather than a sexual threat, though like many other male characters he offers a further source of viewing pleasure to a “female gaze.” There is a sexual tension between him and Buffy from their first meeting. Eventually he asks her out on a date, and in “First Date” Buffy describes him as “a young, hot principal with earrings” (I read his earrings as a signifier of the exotic; see also chapter 6 on Mr. Trick). He becomes even more sexualized through his interaction with Faith, and liberal values are connoted by his interracial relationships (Gill [2003] notes that by season 7 all the main characters are or have been interracially dating). Yet he does not display the sexual jealousy that marks Xander and Oz; he endorses romance relationships between equals and allows Faith to take the lead in their sexual encounter. This may be partly owing to age: he admits that he has grown out of some of his younger, more aggressive behavior (such as an “avenging son phase” in his twenties [“First Date”]).

[43] Gill offers an insight into fan interaction with the show when she describes how a Web site called The Principal Wood Deathwatch was set up by black female viewers after Wood’s first appearance on Buffy, in the expectation that, as a character of color, he would shortly be killed (2003). The show also intimates that Wood may be a villain. His early appearances are often accompanied by menacing music, he is shown finding Jonathan’s body in the school basement and then burying it in secret (“Never Leave Me” 7009), and, as Buffy says, “He’s got that whole too-charming-to-be-real thing going on” (“First Date”). These expectations are reversed, as regular viewers might expect, when Wood reveals to Buffy that he is the son of a Slayer.11 Unlike Giles, Wood’s presentation is uncomplicated by a “parental” role, and his late appearance means that he has an openness that allows his character great potential (as with some of the bad girls): he is both a man and a new man, perhaps the first in Buffy. Notably, however, he is also still a real man, and he remains Other since he is allied with Others (Giles, foreigner; Faith, working class); again openness is a consequence of marginality.

[44] Some representations of masculinity in Buffy seem able to transcend gender binaries, but on closer examination their masculinity retains traditional elements, and almost all of the new men display a split personality or tension that reinforces a binary structure. New men try to repress “natural” masculine tendencies in themselves (Korsmeyer [2003: 165] describes Giles as “[h]abitually on guard against the resurgence of his old ‘Ripper’ self”), though this is not always successful. Male characters can either retain their masculinity and be classed as the enemy and be defeated by the Slayer, or they can give up their power and be classed as allies and become feminized (Slayerettes—changed later to Scooby Gang). Many new men relate to Buffy as potential partners, and because of this, just like the tough guys, they are in competition with Buffy and with each other (especially with Angel) and their very heterosexuality marks them as complicit with patriarchal structures. Even Jonathan demonstrates this in “Superstar” when he uses an “augmentation” spell to construct a new-man superstar version of himself but unwittingly creates its antithesis, a monster that violently attacks innocent people (mainly women): the new man cannot exist without the old monster masculinity. All the new men are aware of how masculinity is constructed and therefore of how they differ from its traditional form.

[45] This does not prevent every new man from simultaneously being presented as a real man who has to/is able to prove this, especially through sexual prowess or aggression. Masculinity is further asserted by wage earning: of the males in the group, Giles, Xander, and Wood all have paying jobs. Just as Parker and others did, Xander, Oz and Giles may “play the sensitive lad,” but they are as capable as tough guys and monsters of unbridled sexual appetite, damaging sexual jealousy, unthinking violence, or removing female agency. The presentation of “uncharacteristic” traditional masculine behavior in new men is often deflected by comedy. All of this may be a strategy to show that new men do not have to “lack” the attributes of real men, and therefore to make them more appealing to viewers, but it also closes down some of their potential for a revisioning of masculinity. The audience may laugh at Xander’s difficulties in trying to be a new man, but there is no real indication that he will ever become one; Wood retains his potential only through his limited development. The new men are valorized through their contrast with “bad” tough guys, but they are clearly not a solution. They demonstrate again the difficulty in negotiating a new type of gender identity, in trying to construct a masculinity that fits the postfeminist age.

Notes

1. A certain naïveté is implied by the fact that he does not understand the “bees”—sexual metaphor eludes him.

2. Given subsequent rhetoric about Spike/William being “beneath” Cecily and Buffy, this positioning is interesting.

3. Thanks to the responsive audience to my paper at WisCon 25 (2001) for raising some of these points in discussion.

4. In this respect Giles also plays out the notion of the repressed Brit.

5. Whedon notes “the sexiness and wit Tony Head brought to the role of Giles. . . . As a result, Giles became much more than ‘boring exposition guy’ (“Hellmouth”)” (in Lavery 2002a: 13).

6. The interracial relationship may have seemed edgy in the U.S. (though not in the U.K.), but that both characters are British distances their relationship from American “norms.”

7. Tony Head left the show because he wanted to spend more time with his family in the U.K., but this also fits the “growing up” narrative arc.

8. “It’s sad. She’s got two jobs: Denny’s waitress by day, Slayer by night, and Angel’s always in front of the TV with a big blood belly. And he’s dreaming of the glory days when Buffy still thought this whole creature of the night routine was a big turn-on.”

9. Tom DiPiero suggests that white masculinity itself can be seen as a lack of identity (in Dyer 1997: 212).

10. In the light of Wood’s cooperation with Giles and Giles’ comment about “personal vengeance,” it is perhaps surprising that Giles’ similar situation with Angelus in season 2 is never mentioned.

11. Of course, there is precedent for a black vampire hunter, and Wood’s hidden cabinet full of bladed weapons may refer to it. The comic book character Blade became widely known via the 1998 movie and its sequel. Blade’s mother is highly important in this film: she is also killed by a vampire.

Bibliography

Anderson, Wendy Love. 2003. “Prophecy Girl and the Powers That Be: The Philosophy of Religion in the Buffyverse.” In Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, ed. James B. South, 212–226. Peru, Ill.: Open Court.

Buttsworth, Sara. 2002. “‘Bite Me’: Buffy and the Penetration of the Gendered Warrior-Hero.” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 16.2: 185–199.

Dyer, Richard. 1997. White. London: Routledge.

Edwards, Lynne. 2002. “Slaying in Black and White: Kendra as Tragic Mulatta in Buffy.” In Fighting the Forces: What’s At Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, ed. Rhonda V. Wilcox and David Lavery, 85–97. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gill, Candra K. 2003. “’Cuz the Black Chick Always Gets It First’: Dynamics of Race in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Unpublished paper, WisCon 27, Madison, Wisconsin.

Golden, Christopher, and Nancy Holder. 1998. Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Watcher’s Guide. New York: Pocket Books.

Held, Jacob M. 2003. “Justifying the Means: Punishment in the Buffyverse.” In Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, ed. James B. South, 227–238. Peru, Ill.: Open Court.

Holder, Nancy, with Jeff Mariotte and Maryelizabeth Hart. 2000. Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Watcher’s Guide Volume 2. New York: Pocket Books.

Jarvis, Christine. 2001. “School Is Hell: Gendered Fears in Teenage Horror.” Educational Studies 27.3: 257–267.

Kimmel, Michael. 1997 [1996]. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: Free Press.

Korsmeyer, Carolyn. 2003. “Passion and Action: In and Out of Control.” In Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, ed. James B. South, 160–172. Peru, Ill.: Open Court.

Lavery, David. 2002a. “‘Emotional Resonance and Rocket Launchers’: Joss Whedon’s Commentaries on the Buffy the Vampire Slayer DVDs and Television Creativity.” Slayage 6 (September), 57 pars. 17 January 2003. <http://www.slayage.tv/essays/slayage6/Lavery.htm>.

Levine, Michael P., and Steven Jay Schneider. 2003. “Feeling for Buffy: The Girl Next Door.” In Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, ed. James B. South, 294–308. Peru, Ill.: Open Court.

Mendlesohn, Farah. 2002. “Surpassing the Love of Vampires: Or, Why (and How) a Queer Reading of the Buffy/Willow Relationship Is Denied.” In Fighting the Forces: What’s At Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, ed. Rhonda V. Wilcox and David Lavery, 45–60. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Owen, A. Susan. 1999. “Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Vampires, Postmodernity, and Postfeminism.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 27.2: 24–32.

Robinson, Victoria. 1996. “Heterosexuality and Masculinity: Theorising Male Power or the Male Wounded Psyche?” In Theorising Heterosexuality: Telling It Straight, ed. Diane Richardson, 109–124. Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press.

Sakal, Gregory J. 2003. “No Big Win: Themes of Sacrifice, Salvation, and Redemption.” In Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, ed. James B. South, 239–253. Peru, Ill.: Open Court.

Saxey, Esther. 2001. “Staking a Claim: The Series and Its Fan Fiction.” In Reading the Vampire Slayer, ed. Roz Kaveney, 187–210. London: I. B. Tauris.

Sayer, Karen. 2001. “‘It Wasn’t Our World Anymore. They Made It Theirs’: Reading Space and Place.” In Reading the Vampire Slayer, ed. Roz Kaveney, 98–119. London: I. B. Tauris.

Simkin, Stevie.2004a. “‘You Hold Your Gun Like a Sissy Girl’—Firearms and Anxious Masculinity in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Slayage 11-12 (April), 27 pars. 12 August 2004 <http://www.slayage.tv/essays/slayage11/Simkin_Gun.htm>.

———. 2004b. “‘Who Died and Made You John Wayne?—Anxious Masculinity in Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Slayage 11-12 (April), 36 pars. 12 August 2004 <http://www.slayage.tv/essays/slayage11/Simkin_Wayne.htm>.

Torres, Sasha. 1993. “Melodrama, Masculinity, and the Family: thirtysomething as Therapy.” In Male Trouble, ed. Constance Penley and Sharon Willis, 283–302. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press.

Williams, J. P. 2002. “Choosing Your Own Mother: Mother-Daughter Conflicts in Buffy.” In Fighting the Forces: What’s At Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, ed. Rhonda V. Wilcox and David Lavery, 61–72. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Woloch, Nancy. 2000. Women and the American Experience. 3rd ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.