Kelly Kromer

Silence as Symptom:

A Psychoanalytic Reading of “Hush”

[1] In the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, language is used to both create a fictionalized world and allow the characters some control over that world. The way the Scooby gang speaks contributes to the way they (and we) experience Sunnydale. Language is a powerful weapon in Buffy, and its main use is to structure the reality of the television show. Within the fictional framework of Sunnydale, Buffy acts as Lacanian law. She creates the world around her by classifying Sunnydale’s inhabitants as either wicked or good and doling out punishment accordingly. Buffy’s power comes from both her superhuman strength and her ability to banter with the monsters and demons. In their chapter “Staking in Tongues: Speech Act as Weapon in Buffy,” Overbey and Preston-Matto note that “Buffy is the speech act. She is the utterance that communicates meaning. . . . she is embedded in language. . . . she embodies language” (83). Buffy, when acting as an effective slayer, is able to observe Sunnydale and classify its inhabitants as either good or evil. In this way, Buffy catalogs and classifies Sunnydale, thus structuring the world around her[1]. Language structures Buffy’s universe, but in the fourth season’s silent episode, “Hush,” this structuring force is removed and Buffy must act without language. Lacan’s schema L and his central tenet that the Law results in desire can help to untangle the silent knot that is “Hush.”

[2] While Freud used the terms id, ego, and superego to describe the workings of the mind, Lacan defined internal and external influences that shape the psychoanalytic subject.[2] He posited that humans are under the influence of three orders: the Symbolic, a place of language and cultural control; the Imaginary, where fantasies, projections, and identifications produce what we call reality; and the Real, an unconscious, unknowable, and indescribable realm[3]. Lacan makes a definite distinction between “reality” and the Real, and while psychoanalytic subjects consciously experience the world in Imaginary reality, our true desires reside in the Real. These three orders shape and impact each other; our secret desires are a product of the restrictions and taboos issued from the Symbolic, and these desires are filtered and fitted into Imaginary reality. Language structures the reality of the psychoanalytic subject, communicating cultural codes of conduct and policing the actions of individuals. As such, the Symbolic is the place of the law. It is only through entry into the Symbolic system that a human becomes part of society. Participation in the Symbolic allows one to become part of the social group, and subordination to the system and its various prohibitions feeds and fuels desire.[4] Lacan states in his Ethics of Psychoanalysis that he “’would not have fancied to lust for the Thing if the law hadn’t said Thou shalt not lust,’” and he illustrates this relationship between prohibition and desire using his schema L. The schema L begins at Symbolic language that produces a desire that only fully exists in the unconscious (the Real). Unconscious desire is sublimated or displaced, leading to a symptom—the observable side of the psychoanalytical object. The symptom, as the conscious object of an unknowable desire, can never be completely fulfilled.

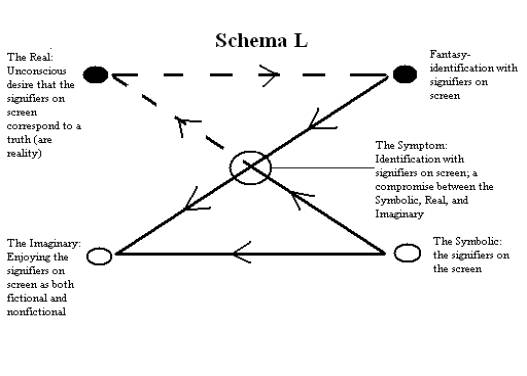

[3] The writers of Buffy the Vampire Slayer use language to create a new fictional reality. This fictional reality is the first layer that can be described using Lacan’s schema L:

This schema describes how and why television is an effective medium that can make an audience feel love, hate, joy, and in Buffy’s world, fear. The images themselves, the signifiers we see on the screen, reside in the Symbolic dimension. These signifiers, encapsulated in the box of the television, are obviously not anything more than images (we do not believe miniaturized people actually live in the box).[5] The knowledge of this fictionalization of signifiers acts as the law in this scenario, dictating how we see, understand, and interact with television. But knowing the governing forces of television’s signifiers is not the same as accepting those forces. The obvious fiction of these images produces a desire for those images to be non-fiction, resulting in a fantasy that the signifiers do exist outside of the television set. A compromise must be met in order for the audience to enjoy watching television—we must identify with the images, convincing ourselves that fiction may be somehow connected with our world. This desire for the images of television to be somehow non-fictional is most apparent in our obsession with “reality TV.” The images themselves produce the desire for those images to hold truth. The way signifiers of television function on the imaginary axis allows the images, shows, and characters to affect us. These signifiers must exist in the Symbolic, Real, and Imaginary realms as a compromise between the three. Without the desire for the fictional images to be non-fictional, “Hush” and other scary shows would not work.

[4] While Lacan’s schema L is helpful in explaining why we identify with the signifiers of television, Freud may offer a clue as to why other episodes of Buffy are not as unsettling as “Hush.” Freud discusses how fictional works can produce eerie or scary effects in his text “The Uncanny.” He separates what happens in fiction and literature from what happens in our (in Lacan’s terms) Imaginary reality. Freud sees the difference between fiction and reality as a difference in expectations. We expect our reality to function following certain laws—monsters do not exist, people do not have magical powers, one cannot see into the future, and we cannot come back from the dead. In literature, however, it is the reality the author writes or depicts that holds force. The rules governing the worlds of novels, plays, fairy tales, and myths are different from the rules of our own reality, and the rules governing these worlds are decided upon by the author. Magic and monsters are possible in Joss Whedon’s world of Sunnydale; as a result, the occurrence of magic or the appearance of monsters does not seem out of the ordinary. Freud tells us that “we adapt our judgment to the conditions of the writer’s fictional reality and treat souls, spirits and ghosts as if they were fully entitled to exist, just as in our material reality” (156). As he goes on to say, “many things that would be uncanny if they occurred in real life are not uncanny in literature, and that in literature there are many opportunities to achieve uncanny effects that are absent in real life” (156). One such opportunity to achieve an uncanny effect occurs in “Hush.”

[5] The writers of Buffy the Vampire Slayer use language as a structuring force in their show. Buffy’s and her friend’s constant manipulation of language serves to set up the boundaries of the show. As long as Buffy can refer to season one’s “Big Bad” as “fruit punch mouth,” the audience knows that she is still able to fight. Words have power, and in Buffy the “tongue is as pointed as the sword” (Overbey and Preston-Matto 84). Buffy’s wordplay is just as common in the show (especially in times of duress) as her physical fight scenes; the two interact to highlight Buffy as capable and in-charge. Overbey and Preston-Matto continue, telling us that “words and utterances have palpable power, and their rules must be respected if they are to be wielded as weapons in the fight against evil” (73). Buffy is the law in both deed and word. But the rules of Buffy’s universe change during “Hush.” Without her voice, Buffy cannot make the cutting remarks that once indicated to the audience that she was in control. While she still must function as the law in Sunnydale, dealing out death and deciding who is good and who is evil, she suddenly must fulfill this role outside of language. Silence in any television show might feel a bit disconcerting, but in Buffy the silence is downright uncanny precisely because so much of the show’s universe is built on the characters’ ability to use and control language.

[6] “Hush” introduces the theme of language throughout the first act of the episode. In the first scene of the show, Buffy’s psychology teacher’s lecture centers on language. Dr. Walsh makes a difference between “communication” and “language,” telling her students that the two are different things. Before everyone’s voices are stolen, there is too much talking and absolutely no communication: Riley and Buffy cannot communicate because all they do is “babble;” Willow’s Wicca group, a group of “wanna-blessed-be’s,” only talk; and Spike won’t shut up when Xander tries to sleep. In her conversation with Willow, Buffy comments on her inability to talk with Riley the way she wants to, telling her friend “every time we talk, I have to lie.” Buffy and her friends seem, at least on some level, to realize that language structures reality. Each character is frustrated by the inability to shape experiences effectively. This is especially true for Buffy, who, while usually able to throw demons off their game by using witty banter, cannot interact successfully with Riley using language. While everyone seems frustrated by language at first, when speech is taken away the silence is unnerving. “The absence of language in “Hush” is a helpless horror: unable to speak to each other, the Slayer Squad cannot fight” (Overbey and Preston-Matto, 74). Sounds become magnified— the crying in the hallway, shattering of a glass, sound of the footmen’s chains, news broadcast, and Maggie Walsh’s automated voice—all contribute to the spooky feel of the episode. Sounds that would have only existed in the background as white noise suddenly take center stage, and the audience feels the absence of language even more strongly.

[7] While the silence of the episode is uncanny, “Hush” also taps into common childhood fears through its portrayal of The Gentlemen. Giles describes The Gentlemen as “fairy tale monsters” and Buffy’s prophetic warning—“Can’t even shout, can’t even cry. The Gentlemen are coming by. Looking in windows, knocking on doors. They need to take seven and they might take yours”—has a haunting nursery rhyme quality. The Gentlemen are old, white, Victorian, ultra-polite, well-dressed, clean, and precise. As such they tap into childhood fears of adults and old age, medicine, surgery, and the unwanted penetration of one’s body. As Rhonda Wilcox notes, The Gentlemen “symbolize mortality and something about sex” (151). The Gentlemen’s Victorian look combined with their shiny metal teeth and scalpels highlights a fear of industrialism (and historically links these monsters with a Freudian or more general psychoanalytic reading). The fact that The Gentlemen have to repeat their gruesome surgery seven times is reminiscent of another aspect of Freud’s uncanny- the compulsion to repeat. Everything associated with The Gentlemen is nightmarish. The old Victorian clock tower they use as a home base suddenly appears in Sunnydale, and their henchmen are gimp-like personifications of the tension between sanity and insanity (they are dressed in straightjackets that have come undone). Their arms hang down at their sides like primitive apes, and their animal-like behavior further contributes to the horror. The fears that these silent monsters access bring us back to Freud again: the “uncanny is what one calls everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden and has come into the open” (132). The Gentlemen’s sudden unexplainable appearance in Sunnydale is very much like a nightmare, and it is highly significant that Buffy first encounters them within a dream (cf. Wilcox 152-54). The nightmarish, dreamy quality of The Gentlemen and the episode in general seem to indicate a regression from the logic of Imaginary reality. When the town wakes up unable to speak, they regress to an infant-like position, and as such are more susceptible to the nightmare of “Hush.”

[8] The Gentlemen function by stealing all the voices of Sunnydale’s residents, capturing and housing speech in a wooden box until the end of the episode. According to Buffy’s dream, they want to steal seven hearts while the townspeople are rendered mute. The importance of language becomes truly apparent—the people of Sunnydale have no idea what’s going on, they can’t speak to each other or hear the cries of attacked residents. Without access to language, the town is left with only non-verbal forms of communication. Signifiers on message boards substitute for conversation. They cannot scream when chased by monsters or yell for help when attacked. If we position language as Lacan does in the Symbolic and accept language as a structuring force, then the silence of Sunnydale produces a shifted fictional reality. In the instant the ability to speak is taken away from the townspeople, the Imaginary is turned upside down—the Real reigns supreme while the Symbolic becomes fictionally inaccessible and societal Law begins to disintegrate. Lacan states in Écrits, “it was certainly the word (verbe) that was in the beginning, and we live by its creation” (61). The Imaginary axis produced through the interaction of Symbolic language and the Real begins to break down, and the protection it once provided from the Real disappears. Without the power of words, Buffy is left without one of her main weapons. Buffy must speak in order to destroy The Gentlemen and reassert the Symbolic order; making the Real symbolic provokes the destruction of the Real: in Lacanian terms, “the symbol manifests itself first of all as the murder of the thing” (104). Buffy, in the position of Giles’ princess[6], must reassert her power over The Gentlemen, and just as the monsters violate their victims, Buffy’s voice violates them. As Buffy screams The Gentlemen cover their ears—and then their heads explode.

[9] While the town cannot speak, Lacan’s realm of the Real takes over. It is an indescribable world not only because the townsfolk literally cannot speak, but also because The Gentlemen cannot be readily described. They are the scariest monsters of the series, so removed from reality that they do not even walk on the ground but float just above it. While they steal the voices of the townspeople, they are also silent themselves—communicating with nods, hand gestures, and gruesome smiles. Disconnected from language, they are also disconnected from reality. Because they are described as “fairy tale” monsters, the link to the Real is even more apparent. These are the monsters that inhabit the stories we tell children to get them to listen to their parents, the monsters that we seem secretly to desire to know. They cannot be described—when Giles tries to explain who they are he must use primitive drawings that are not easily interpreted by the group.

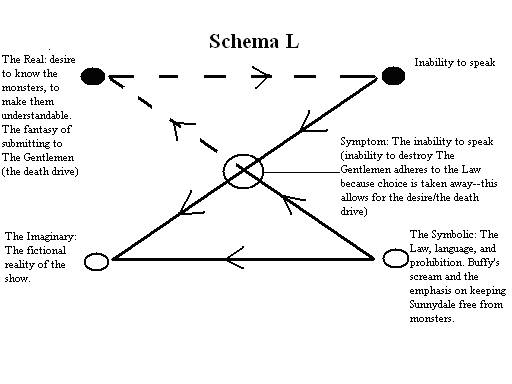

[10] While the world of The Gentlemen is situated in the Real, Buffy herself can be viewed as a personification of the Symbolic order. The Symbolic shapes imaginary reality, and Buffy is the character who shapes Sunnydale. As “The Slayer” (a powerful signifier that marks her as a chosen superhero), Buffy must act as the law. She decides who will live and who will die, and her character is always doubly inscribed. Buffy is the law but does not want to be (a symptom of personifying the symbolic order)—she has superpowers but constantly communicates her desire to be a “normal” girl. Within the fiction of the television show, I would place the following in Lacan’s Real, Imaginary, and Symbolic orders:

Real = there is… = the death drive/the desire to know the monsters

Imaginary = there is similarity = fictional reality of Sunnydale/the Hellmouth

Symbolic = there is difference = Buffy as “The Slayer”/ the Law

I derive the above placement from Lacan’s schema L:

[11] On the right bottom point of the schema, there is the Symbolic, including language, prohibition, and Buffy’s scream[7]. Buffy as a fictional personification of the Symbolic order is charged with protecting Sunnydale from monsters and keeping the townspeople from being murdered. Buffy’s prohibition of monsters and murder produces an unconscious desire for those things—producing the fantasy of submitting to the monsters and the death drive. The town’s inability to speak is the symptom, a compromise between the Symbolic law and the Real, and a regression into a world of childhood nightmares. This symptom allows the townspeople to fear The Gentlemen while not having the ability to destroy them. It is interesting to note that the newscaster reports on Sunnydale’s silence as a possible “epidemic” of laryngitis and tells us that “The Center for Disease Control has ordered the entire town quarantined…until the syndrome is identified or the symptoms disappear” (emphasis mine). With the power of language taken away from them, they are able to submit to the fantasy in the Real; their silence is the symptom of this desire. The only way to overcome this bout of laryngitis is through Buffy’s interdiction. She, as the law, must scream, thus rejecting The Gentlemen and providing an entry point back into language. It is important that The Gentlemen can only be destroyed after Buffy can speak. As the law, she must wield both physical and verbal power to defeat The Gentlemen. Overbey and Preston-Matto comment, “Simultaneous physical and verbal combat gives Buffy twice the power for her punch” (76). Silent Buffy is armed with only half her arsenal, and therefore she is only half as powerful.

[12] The way The Gentlemen remove the hearts of their victims can also be linked to authoritative paternal knowledge and the incest taboo (at least as a motif of bodily violation). Wilcox, when discussing the “threshold” imagery of “Hush,” links The Gentlemen’s entry into the homes and bodies of their victims to sexual penetration. This “sexuality” of The Gentlemen is even more disturbing juxtaposed to the sterility of their operations. These monsters do not tear or rip hearts from bodies; instead they remove them expertly with scalpels. They keep themselves clean, allowing their henchmen to do the messy work of pinning the victim down (Wilcox 150, 153). They carry their tools in old-fashioned medical bags and congratulate each other with silent claps after successful operations. In this way, they display an authoritative knowledge of the human body and medical practices, but it is knowledge turned sour—a desire to gain access to the innards of their victims. The prohibition of incest is the prohibition of a sexual desire. This prohibition occurs when someone says “no.” Without Symbolic language however, The Gentlemen are not prohibited. They force their way into the inner recesses of their victims, violating their body cavities in order to destroy them. The Gentlemen’s violation of their victim’s bodies should be read as a sexually aggressive act. When the audience actually gets to witness the operation, the victim we see is held tightly down to a bed while he screams silently.

[13] Not only are The Gentlemen’s actions sexualized in the episode, the silence of “Hush” also allows Buffy’s own sexual desire to be explored. Recalling the discussion of the schema L above, Buffy herself experiences the unconscious desire to submit to the death drive and The Gentlemen. As the keeper of the law and order, a desire for death, destruction, and chaos is produced. Buffy dies twice during the course of the series, and the second time she greatly regrets being brought back to life. Not only does her life revolve around death, her sexual relations do as well. Two of her three major love interests are vampires—the undead personifications of her unconscious desire. Discussing Buffy’s first romantic vampire interest, Krimmer and Ravel assert that “though the obstacles imposed upon the lovers seem to foreclose any hope for intimacy; they are, paradoxically, the very features that sustain the couple’s relationship” (159). But Lacan argues that the production of desire through interdiction is not a paradox, it is instead a necessary aspect of sexual relations. Krimmer and Ravel go on to note that “the deferral of desire not only is at the heart of Buffy and Angel’s relationship but also the structural principle of the show itself” (159). This structural principle can be seen even in Riley, the one everyone thought was normal. He turns out to have a dark side, and Buffy seems unconsciously to know this. Perhaps this knowledge is most apparent in the opening dream sequence of the episode; when Buffy finds the young girl singing the warning, Riley is standing behind her, as he touches her shoulder and she begins to turn around, he turns into one of the monsters she will have to fight. While Riley is connected to powerful institutions (as a teaching assistant at the university by day and a covert commando by night), he also has a dark side (which is even more apparent later in the season when he begins visiting vampire dens and allowing himself to be bitten). But even the light and dark sides of Riley are not enough for Buffy; there is something more that she desires. Later in the series, when she finds herself in a sadomasochistic relationship with Spike, a vampire, the audience sees her unconscious desire for death (here literally the undead) even more clearly. Buffy, as keeper of order and life, desires chaos and death. While she does not normally exhibit a symptom of this desire in her work slaying monsters (with the exception of her own silence in “Hush”), she does in her sexual relations.

[14] “Hush” is one of the most disturbing episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The episode is truly scary not only because The Gentlemen are downright spooky, but also because it throws us, as audience members, off balance. It is an example of what Freud would call the uncanny—something that is counter to what should be. In Buffy, language normally serves as a structuring force of the show and speech is one of Buffy’s favorite weapons; therefore, when language is taken away the rules of this fictionalized reality are thrown off-kilter. Neither the audience nor the characters know exactly what is going on, but everyone realizes that swords and crossbows will not be enough to defeat The Gentlemen. What’s missing from the arsenal is the speech act itself—without it the social order begins to become chaotic and unstructured. Buffy must find an entry point back into the Symbolic through her voice. But before she can defeat The Gentlemen in this way, we all are reminded of how powerful the latent forces of Lacan’s Real can be.

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny.” In The Uncanny, translated by David McLintock. New York: Penguin, 2003. 121-162.

“Hush.” Writ. and dir. Joss Whedon. Buffy the Vampire Slayer. WB. 14 Dec. 1999.

Krimmer, Elizabeth, and Shilpa Raval. “’Digging the Undead’: Death and Desire in Buffy.” Fighting the Forces: What’s at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Ed. Rhonda Wilcox and David Lavery. Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield, 2002. 153-64.

Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: A Selection, translated by Alan Sheridan. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1977.

___. The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, translated by Dennis Porter. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992

Leupin, Alexandre. Lacan Today: Psychoanalysis, Science, Religion. New York: Other Press, 2004.

Overbey, Karen Eileen, and Lahney Preston-Matto. “Staking in Tongues: Speech Act as Weapon in Buffy.” Fighting the Forces: What’s at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Ed. Rhonda Wilcox and David Lavery. Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield, 2002. 73-84.

“Prophecy Girl.” Writ. and dir. Joss Whedon. Buffy the Vampire Slayer. WB. 2 June 1997.

Wilcox, Rhonda. “Fear: The Princess Screamed Once. Power, Silence, and Fear in ‘Hush.’” Why Buffy Matters: The Art of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. New York and London: I.B. Tauris, 2005. 146-161.

[1] When Buffy is less effective as “The Chosen One” however, her ability to structure the world through language is diminished. This is painfully the case in season seven, in which Buffy’s incessant speeches have little effect. Buffy’s inability to use language makes sense within the context of the season’s story arc, in which Buffy must transform from The Chosen One to one slayer among many. As her status as The Slayer begins to diminish, her ability to structure Sunnydale through language does as well and she is forced to obtain a weapon from Caleb to supplement her physical strength.

[2] If a correlation were to be made between Lacan’s and Freud’s terminology, however, the id would be closest to the Real, the ego to the Imaginary, and the superego to the Symbolic.

[3] The Real, while unknowable, is also the place of individuality, a place unique to each subject.

[4] Desire, as opposed to natural, animalistic drive, is the product of interdiction. For one to desire a thing, that thing must be placed “off-limits.” It is similar to what happens when a friend orders you not to think of an elephant—you can’t think of anything else.

[5] Editors’ note: Pace Buffy in “Beer Bad” (4005).

[6] Wilcox notes that Buffy “expects to take the role of the princess” (148). Because Buffy generally takes on the role of protector her assumption here is not too surprising. When she fulfills the role of the princess however, the scream she destroys The Gentlemen with is “purposely not princess-like” (Wilcox 150). This makes sense within the series as a whole—Buffy is not usually characterized as girly-girl princess-y when fighting monsters—and within a psychoanalytic reading of the episode itself—her scream is the exit mechanism out of the monster’s nightmare realm of the Real and back into the Symbolic; a place where Buffy’s role is decidedly not that of a fairy tale princess.

[7] Language can be read as the entry point into the Symbolic. It is through language that one is given the “rules” of society—especially specific prohibitions. Language serves as both the ability to prohibit and the ability to protest. When the town is unable to speak they are unsuccessful in fending off The Gentlemen.